Support For Industry Placement Mentors

5. Communication

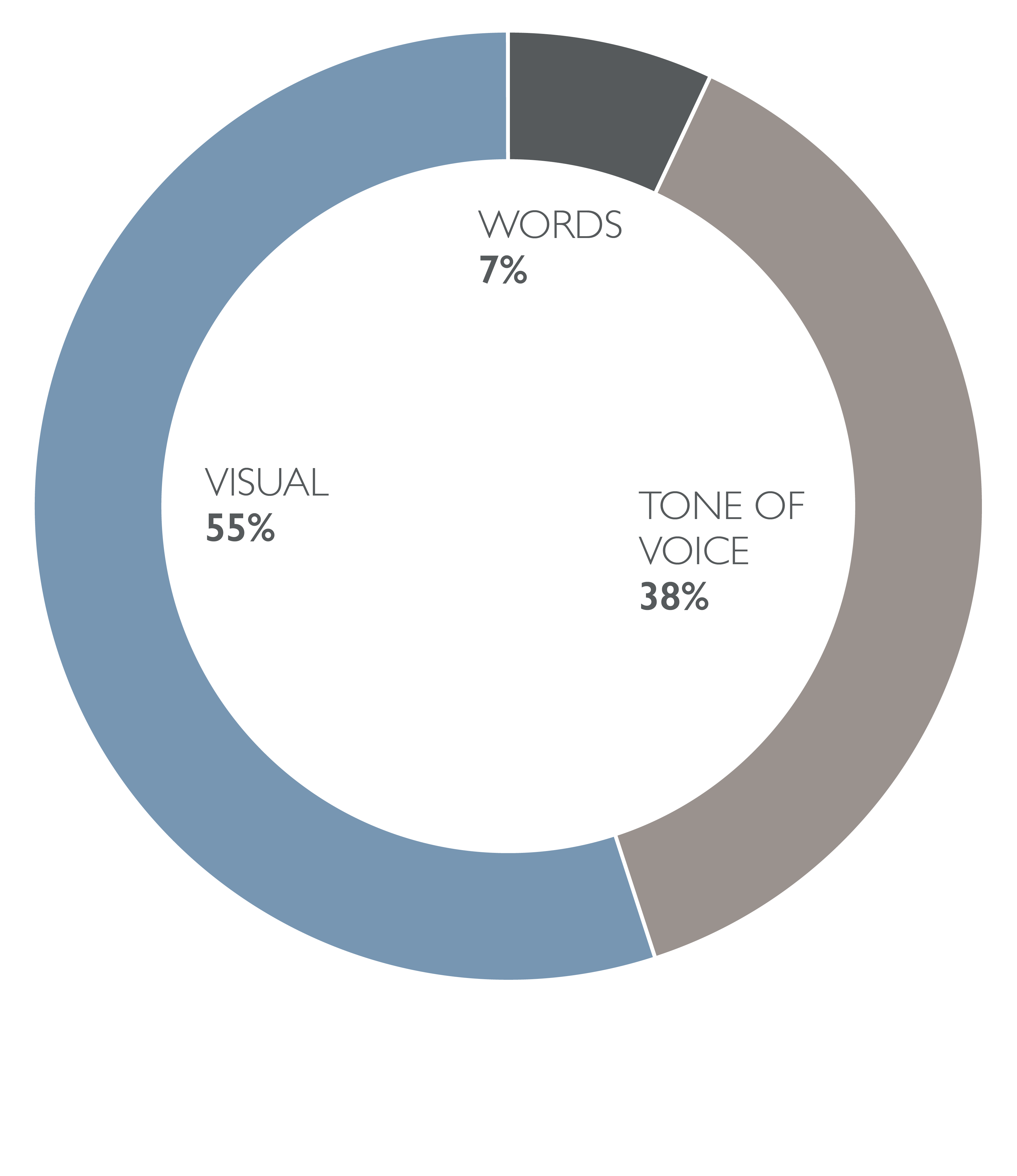

Communication is a two-way exchange. When thinking about communication skills we tend to focus on how to get across what we want to say and presenting our ideas carefully. The other side of the exchange is just as important, though: how to listen properly to what other people are saying, interpret it accurately and get a genuine dialogue going.